June 24, 2009

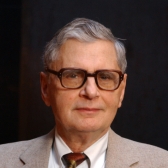

Fritz Gluckstein discusses life immediately after World War II in Berlin and his eventual immigration to the United States. Born to a Jewish father and Christian mother, he was classified under Nazi law as Mischlinge, of mixed ancestry, or part Jewish. He spent the war in Berlin assigned to various forced labor battalions.

LISTEN

Esta página también está disponible en español.

TRANSCRIPT

FRITZ GLUCKSTEIN:

It wasn’t everything rosy. Berlin was destroyed–no electricity, no heat, we had to go out to the woods to get our own heating wood.

NARRATOR:

Over 60 years after the Holocaust, hatred, antisemitism, and genocide still threaten our world. The life stories of Holocaust survivors transcend the decades and remind us of the constant need to be vigilant citizens and to stop injustice, prejudice, and hatred wherever and whenever they occur.

This podcast series presents excerpts of interviews with Holocaust survivors from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s public program First Person: Conversations with Holocaust Survivors.

In today’s episode Fritz Gluckstein talks with host Bill Benson about life in Berlin immediately after World War II and his eventual immigration to the United States. Under Nazi law, Fritz was classified as Mischlinge, someone of “mixed ancestry,” and spent the war in Berlin assigned to various forced labor gangs.

BILL BENSON:

When did you know, for sure, that you were safe?

FRITZ GLUCKSTEIN:

Well, I remember, I was–at that time we already lived in the cellar. I went out to try to get some bread. I came back and the Russians were outside the building. And of course we had to persuade them that we were not Nazis. All Jews were [inaudible], but we lived with some other Jewish couples, and we all had to move together.

So we persuaded them that we were Jewish and we realized, well, we had survived the Third Reich.

BILL BENSON:

So the Russians weren’t believing that you were Jews?

FRITZ GLUCKSTEIN:

We had to persuade them that we–well, look, a young man could have been a Nazi out of uniform.

BILL BENSON:

Right, right. What was it like to try to survive once the war was over, amidst the rubble of Berlin?

FRITZ GLUCKSTEIN:

Well of course, it wasn’t everything rosy. Berlin was destroyed–no electricity, no heat, we had to go out to the woods to get our own heating wood. And one week, or one month, the Russians took care of the food supply, dark bread; the next month, the western powers took care of the food supply, white bread.

At that time we moved out to a suburb. We were lucky because we could grow beans in the front and tomatoes in the backyard. We had a front yard and a backyard. And of course at that time, the first care packages arrived.

[They were] very welcome because the currency at that time was cigarettes. If you had cigarettes, you had it made. So I remember, we looked for–all brands of cigarettes were welcome, but Camels, the most valuable, and I still remember forever Lucky Stripe, and what was it, Old Gold, and even Raleigh. But this was absolutely the currency.

BILL BENSON:

And you could barter with that?

FRITZ GLUCKSTEIN:

I remember when I left for the United States, before we entered the boat we were told, “Ladies and gentlemen, once you set foot on the boat, a cigarette is just a cigarette.”

BILL BENSON:

Fritz, did you ever consider taking your revenge on the Germans?

FRITZ GLUCKSTEIN:

Oh, yes. We said, “Oh wait a minute, when that’s over, that so-and-so and so-and-so and so-and-so, we’re going to get him.” Well, once it was over, we didn’t lower ourselves to their level. No, we didn’t do it.

BILL BENSON:

What made you decide to go to the United States, and if you’d stayed, would you have been under the Russian domination?

FRITZ GLUCKSTEIN:

No, actually we happened to be in the American sector. But I felt, after the war, that it wasn’t my duty to rebuild Germany. And before I left, my father told me, “Look,” he said, “If I were ten years younger, your mother and I would go with you. But what can I do over there? The law is completely different, based on old English law. Here it’s based on old Roman law. I can’t practice my profession. But you go.”

But he said, “Fritz, I hope that you choose a profession that is not limited to one country, like law.” Well I didn’t; I became a veterinarian.

NARRATOR:

You have been listening to First Person: Conversations with Holocaust Survivors, a podcast series of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Every Wednesday at 1 p.m. from March through August, Holocaust survivors share their stories during First Person programs held at the Museum in Washington, DC. We would appreciate your feedback on this series. [Please take our First Person podcast survey (external link) and let us know what you think.]

[On] our website you can also learn more about the Museum’s survivors, listen to the complete recordings of their conversations, and listen to the Museum podcasts Voices on Antisemitism and Voices on Genocide Prevention.