-

Learn More about Peter

- Oral History Access Peter's Oral Testimony

Peter J. Stein was born Petr Stein on September 22, 1936, in Prague, Czechoslovakia, to a Jewish father and a Catholic mother. Peter’s father Victor operated a factory that produced bentwood furniture and sporting equipment, and his mother Zdenka worked as a teacher, translator, and office manager.

Peter’s second birthday came in the midst of an international crisis, as the possibility of Nazi Germany instigating a European war loomed. The situation was so serious that the day after Peter’s birthday, Victor, a First Lieutenant in the Czechoslovak army, was sent with other Czech army reservists to the Czechoslovak-German border. But, the crisis was resolved diplomatically, avoiding a European war, but at the expense of Czechoslovakia. In accordance with the Munich Agreement, German forces occupied and annexed the Sudetenland (a border region of Czechoslovakia with a significant ethnic German minority) on October 1, 1938, and Peter’s father returned home less than a week later. In March 1939, Peter and his family witnessed the Nazis’ violation of the Munich Agreement as German troops entered Prague. They created a German occupation administration called the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. Peter’s parents and most of their extended family chose not to try to leave believing they would survive the occupation and life would return to normal.

The Nazis applied the racial categorizations they had established in Germany under the Nuremberg Race Laws in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. Under the Nazi regime, Victor and Zdenka’s marriage was categorized as a “mixed marriage” (“Mischehe”). Peter was considered a “Mischlinge,” meaning mixed-race. Victor’s status as a spouse in a mixed marriage and Peter’s status as a “Mischlinge” had important consequences for them under Nazi rule. For example, in September 1941, all Jews in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia who were six years of age and older had to wear a yellow Star of David badge. This included Victor. At the time, Peter was only 5. But even when he turned 6 he did not have to wear the badge because he was exempt because he was considered a “Mischlinge.”

Beginning in 1941, the Nazi German authorities began to carry out the systematic roundup and transport of Jews from Prague to the nearby Theresienstadt ghetto. In the summer and fall of 1942, Peter’s paternal grandmother, along with several of his aunts, uncles, and cousins, were sent to Theresienstadt. His grandmother Sofie died in Theresienstadt. Peter’s other families were deported from the ghetto to Maly Trostenets killing site near Minsk, and Auschwitz.

Peter’s father was initially spared because he was in a mixed-marriage. However, during the war the German government used intermarried Jewish men as forced laborers. Victor was forced to leave his family and build roads in and around Prague. In 1944, these efforts expanded and many “Mischlinge” and intermarried couples had to perform forced labor. Zdenka, by virtue of her marriage to a Jewish man, was forced to work in a Nazi-controlled factory.

During the occupation with Victor away, Zdenka and Peter lived on their own, supported by meager rations. Peter looked forward to a weekly visit to his Catholic grandparents’ home, where his grandmother, having bartered valuables for extra food, prepared large meals. The family also listened to the BBC, through which they learned about D-Day and other events of the war.

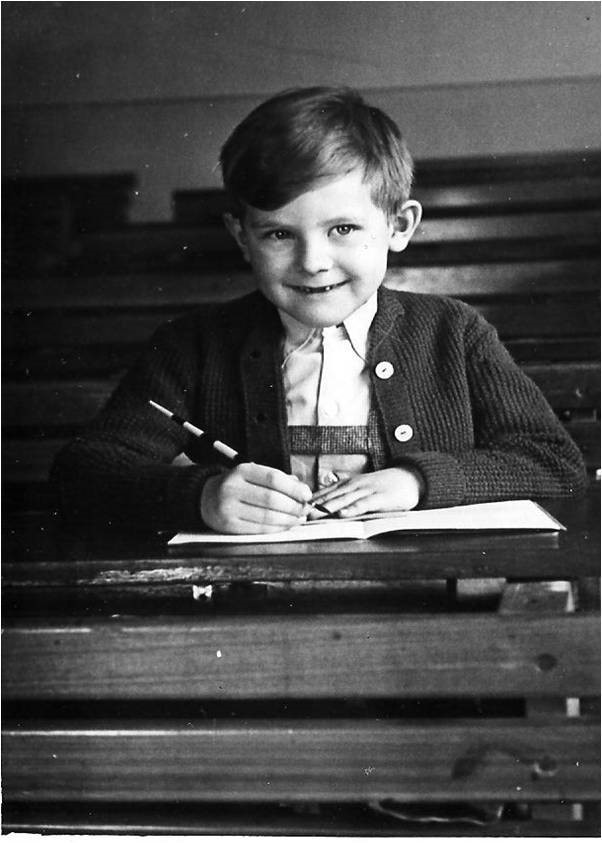

Peter encountered antisemitism from both classmates and strangers. One second-grade classmate targeted and bullied Peter for being Jewish. In the winter of 1943, an SS officer demanded Peter’s seat on a tram on his way to school. Peter was scared that the man might know that his father was Jewish, even though his mother and grandparents had warned him to keep his father’s identity secret. As he walked from the tram to his school, he checked to make sure the SS officer was not following him. He was reassured that he was safe by his teachers, who appeared, to Peter, disinterested in the Nazi propaganda they were required to teach.

In early 1945, the Gestapo ordered that intermarried and “mixed” Jews (mostly men) living in the Greater German Reich (including Prague) be deported to Theresienstadt. Thousands, including Victor, were deported, but many others avoided deportation thanks to wartime chaos and local policy decisions or by going into hiding "underground." Most of those deported to Theresienstadt in this wave survived the war.

In February and March 1945, Peter witnessed bombings from his school and bedroom windows. In May of the same year, Peter witnessed increasing fighting around the city as Czech partisans and the Soviet army drove German soldiers out of Prague. On May 8, 1945, the war in Europe officially ended. The next day, May 9, Peter’s father returned from Theresienstadt. Most of Victor’s family had been murdered in the Holocaust.

After the Czech Communist Party seized power in February 1948, Zdenka and Peter immigrated to the United States. On November 3, 1948, they arrived in New York staying with a sponsoring aunt and uncle until Zdenka found a job as a governess and maid. Victor followed in 1951 after settling business affairs in Prague. Peter attended the City College of New York and then Princeton University, where he earned his Ph.D. in sociology. In 1993, a conversation with his students furthered his dedication to Holocaust education and study. Peter recently published a book about his childhood experiences titled A Boy’s Journey: From Nazi-Occupied Prague to Freedom in America. He lives in Washington, DC, and currently serves as a volunteer at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.