September 02, 2021

By Tahlia Mullen

The ongoing conflict between farming and herding populations in Nigeria exemplifies how climate change can intensify conflict between communities and place certain populations at increased risk of mass atrocities. With global warming now likely to reach 1.5°C within the next two decades, it is essential that governments, international organizations, and civil society groups assess which communities are most at risk of mass atrocities as a result and how that risk can be mitigated. Nigeria is pioneering a new initiative to change how it raises animals for food and other products. If successful, this system could serve as a model for other countries also threatened by farmer-herder violence related to climate change.

Climate change poses a substantial and disproportionate threat to communities across Africa. Temperatures are increasing 1.5 times faster than the global average in the Sahel, an arid region of Africa covering six countries from Senegal to Chad. The resulting scarcity of water and arable land, exacerbated by other factors such as poor land management, intensifies competition between groups for natural resources. As communities vie for control of scarce resources, systematic attacks against specific subsets of the population have proliferated. Such group-targeted violence increases the risk of future mass atrocities in Nigeria. The Early Warning Project notes two ongoing mass killings in Nigeria and recently warned of increased risk for mass atrocities in Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso.

Resource Scarcity and Risk for Mass Atrocities in Nigeria

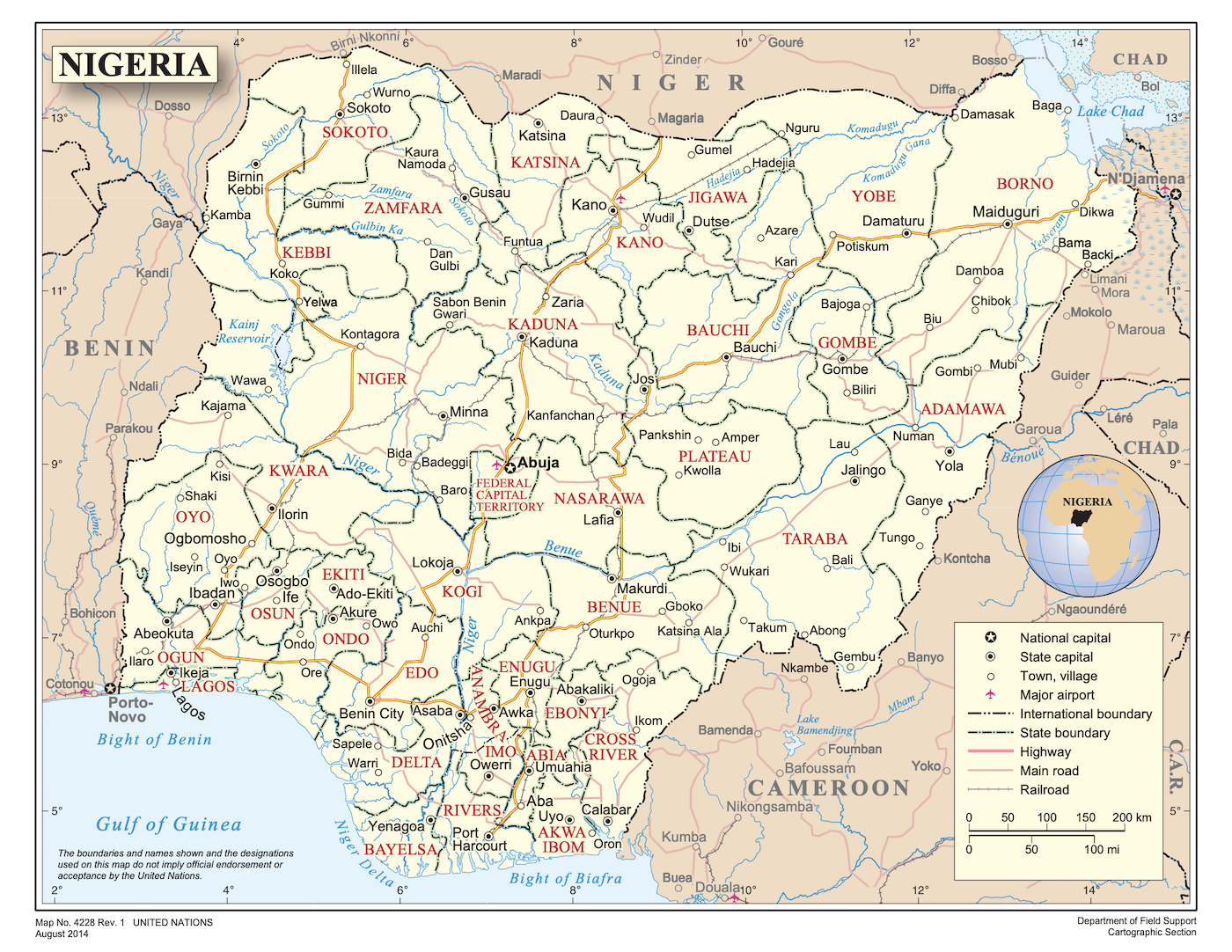

Farmers and pastoralists (nomadic herders) make up over two-thirds of the Nigerian labor force. Many pastoralists are Fulani (also called Peul or Fulbe), a predominantly nomadic and Muslim herder community spread across West and Central Africa. Nigeria’s sedentary farming population is made up of other ethnic groups.

Violent incidents between farming and herding communities have become more frequent in recent decades. Between August 2018 and August 2021, 4,900 Nigerians were killed in the country’s North-Central Zone. The growing scale of group-based attacks puts communities caught in the cross-hairs of land disputes at an increased risk for mass atrocities.

Although it is very difficult to establish a definitive link between a broad, long-term phenomenon like global climate change with conflict trends in a specific location, there are strong reasons to believe that climate change is at least partly to blame for the deterioration of intercommunal relations in Nigeria. A lack of arable land drives competition for control over the country's resource-rich North-Central Zone, provoking violent land disputes and cycles of escalatory violence between the ethnically divided herding and farming communities. In a context where the state security forces do not provide security for the population, Nigerian people are left to fend for themselves. Communities on either side of the ethnic divide form self-defense groups to protect their interests.

Failed Response Measures

Governments have adopted a variety of measures to address the growing conflict between farmers and herders, including passing new laws and deploying national militaries in order to stem violence.

In Nigeria, the North-Central state of Benue passed an anti-grazing law in late 2017 designed to prevent pastoralists from trespassing on farmland. The measure drove thousands of pastoralists into neighboring Nasarawa, where trespassing recommenced and intercommunal violence intensified. The first half of 2018 saw 260 people killed in Nasarawa’s southern region alone.

The federal government responded by deploying the military to Nasarawa and two other states in May 2018. Although security forces dampened the 2018 escalation by ordering militias to vacate, threatening limitless attacks, and killing 100 “criminal elements,” the region is still rife with violent conflict. The centrally located Benue, Kaduna, Plateau and Nasarawa states have seen hundreds of clashes since 2018.

A New Strategy

Acknowledging that the above responses failed to address the root issue of resource scarcity, the Nigerian government changed its tack in 2019 by passing the National Livestock Transformation Plan (NLTP). This ten-year plan aims to transition Nigeria’s livestock sector from a pastoral system to a stationary system of ranching within grazing reserves. By late 2028, the plan aims to create 119 operational ranches and over two million livestock-sector jobs.

The government is spearheading the strategy in seven states prone to farmer-herder violence. It has committed to fund 80% of proposals that would transform farm and grazing lands into ranches and provide technical support to states with plans in place. States have begun allocating land for reserves in preparation.

Is the NLTP Enough?

Despite the plan’s ambitious timeline, no new ranches have been built two years into implementation. Economic constraints and a lack of personnel with robust ranching and preservation management expertise are among the challenges that must first be overcome.

One key obstacle on the path to widespread adoption of the NLTP is herder and farmer distrust. Herders are reluctant to give up their centuries-old pastoral lifestyle and have doubts that ranching is a viable alternative. Meanwhile, farmers fear the NLTP will force them to cede their land for livestock purposes and will unfairly privilege the Fulani community in the long term.

A second obstacle is the ongoing lack of peace and security on ranches. The prevalence of criminal gangs encumbers access to reserve lands and discourages investors from offering support. Additionally, prime grazing land may become even scarcer in the future, threatening the NLTP’s long-term viability.

The NLTP is in danger as the 2023 election approaches, as a new government may decide not to continue its implementation. Success over the next two years is therefore crucial to securing the plan’s long term viability.

Taking the Broad View

Farmer-herder conflict is not unique to Nigeria. Roughly 38 million Fulani herders are distributed across West and Central Africa. Following the 2012 coup in Mali, group-targeted violence escalated between the herder Fulani and farming communities (including the Dogon and Bambara). Lemba Bisimwa, who oversees Mali’s water and habitat projects for the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), identifies climate change as a driver of Malian violence.

More farmer-herder violence may occur as climate change intensifies. Tensions are already rising between the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s pastoral Hema and agricultural Lendu. A June 2019 clash left 160 people dead. Grazing rights were a primary factor in the 2019 attack, and future resource scarcity could exacerbate existing tensions.

The international community should watch Nigeria’s roll-out of the NLTP closely. If the NLTP helps mitigate farmer-herder violence in Nigeria, similar strategies may succeed elsewhere. If the NLTP and similar strategies succeed, foreign governments and international organizations should stand ready to provide financial and operational support where it may be needed.

Equally, global actors should identify other regions where climate change may lead to group-targeted violence and work proactively to prevent conflict such as that seen in Nigeria or Mali from breaking out elsewhere.

Read more on the implications of climate change for mass atrocities.

Tahlia Mullen is a student at Dartmouth College and summer intern for the Early Warning Project.

View All Blog Posts