May 29, 2014

The civil war in northern Mali is flaring anew, and with it, possibly, the risk of mass atrocities.

In a recent post on his War Is Boring blog, journalist Peter Dörrie notes that Tuareg separatists last week beat back an army offensive aimed at retaking Kidal, northern Mali's administrative center. The Malian army pulled out of several other towns in the region soon thereafter.

Unsurprisingly, the fresh fighting is hurting efforts to negotiate an exit from this long-running conflict. As Dörrie observes,

Earlier this year there was at least some hope for a real peace treaty between Bamako and the Tuaregs. The renewed tensions upended any progress the two sides had made. The parties are back to their intractable and uncompromising positions yet again. And they have little incentive to change their attitudes.

This news grabbed my attention because Mali lands near the top in our statistical assessments of the risks of onsets of state-led mass killing, and most mass killings happen in the course of civil wars. Mali is ninth.

Mali ranks so high in our statistical assessments because it is unusually susceptible to coup attempts and new insurgencies, and these threats to rulers' power increase the risk that those rulers (or the ones who toss them out) will use indiscriminate force in an effort to quash them. The present government in Bamako doesn't have features that make it look like a potential mass killer---things like an exclusionary ideology, an authoritarian power structure, and a history of mass violence against civilians---but our modeling and the research on which it's based tell us that those features aren't necessary conditions for mass atrocities to occur.

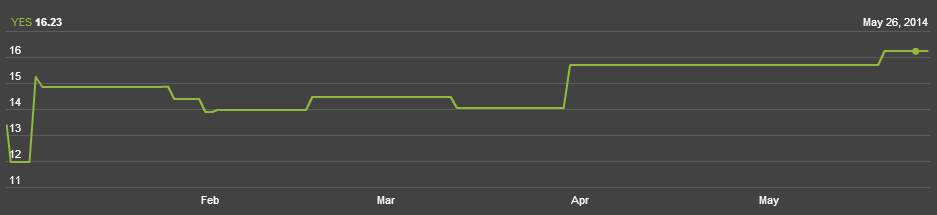

So far, though, our crowd of regional and topical experts is unmoved by the news. Since last November, we've been running the question "Before 1 January 2015, will an episode of state-led mass killing occur in Mali?" on our opinion pool, which elicits and combines probabilistic forecasts from registered participants. As the chart below shows, the (expert) crowd's estimate of the risk of that catastrophe occurring has hovered around 15 percent, with just a couple of small upticks in the past two months.

Our opinion pool's take is broadly consistent with other leading public sources in this field, which don't peg Mali's risk as high as our statistical models do. Neither Barbara Harff's 2013 risk assessments nor the Australia-based Atrocity Forecasting Project, which also uses Harff's genocide/politicide concept as its outcome of interest, identify Mali as a high-risk case. Nor does Mali appear among the cases of "imminent risk" or "serious concern" in GCR2P's most recent R2P Monitor report. Genocide Watch's 2012 Countries at Risk Report--published shortly before the March 2012 coup in Bamako--put Mali at Stage 5 (polarization) on its seven-stage and said that the situation merited close monitoring, but it called out the Tuareg separatists and the humanitarian crisis their rebellion was producing as its primary concern.

Is our pool of experts missing something important, or is it right to keep viewing Mali as modest-risk case in spite of these developments? Please share your thoughts on this question--or other aspects of atrocities risk and prevention in Mali--in the Comments below.

View All Blog Posts