August 11, 2020

By Alex Vandermaas-Peeler, Research Intern

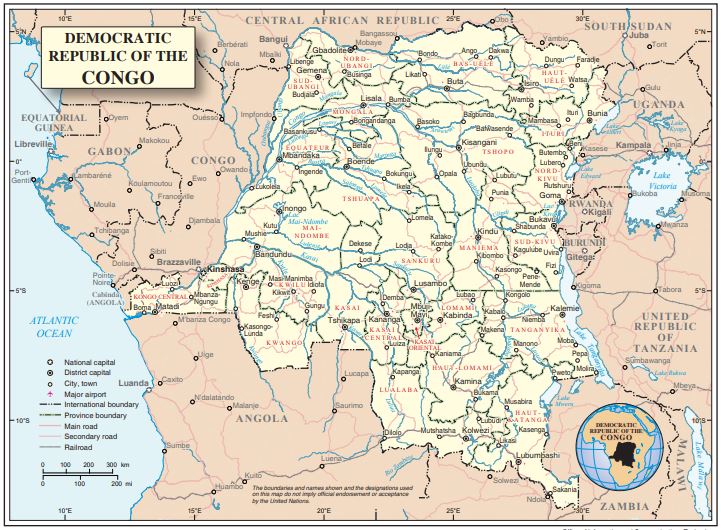

As violence escalates in Ituri province in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), the United Nations (UN) and International Criminal Court (ICC) have raised concerns of possible crimes against humanity. The UN reports deaths have soared in recent months as ethnically-affiliated militias are targeting civilians of other ethnic groups. In addition to high fatality rates, the UN also noted concerns about increases in sexual violence, large-scale displacement, and attacks targeting children. While the violence has worsened in recent months, Ituri has grappled with violence for decades.

According to our Early Warning Project’s Statistical Risk Assessment, the DRC has been experiencing mass killing—perpetrated by either by state or non-state armed groups—continuously since 1993 and is today at high risk for a new mass killing. The Project ranks the DRC 5th highest risk of 162 countries, with a roughly 1 in 7 (13.8%) chance of a new mass killing occuring in 2019 or 2020. In each year since the project began, the DRC has ranked in the top ten highest-risk countries.

Historical Context

Much of the current violence has its roots in unresolved conflicts in the late 2000s. Between 1999 and 2003, Ituri experienced some of the worst violence in the DRC during its two civil wars. Armed groups killed tens of thousands of civilians and committed crimes against humanity, including recruiting and actively using child soldiers, attacking civilians, and committing and commissioning acts of sexual and gender based violence. The conflict quieted significantly when the predominantly ethnically Hema-led armed group Union of Congolese Patriots (UPC) splintered in 2003 and the war formally ended. Despite the official end of the war, more than 140 armed groups are still active in eastern DRC.

Most of the recent violence in Ituri has been perpetrated by militias that tend to be defined along ethnic lines, led by members of the Lendu ethnic farming community, against members of the Hema community and other ethnic groups, like the Alur. Historically, Hema have held more economic power, tracing back to Belgian colonizers placing Hema communities above the Lendu in local hierarchies, creating wide economic disparity between the groups. These divisions persisted after the colonial period and the groups have intermittently fought over land and resources in the last few decades.

Recent Violence

Between October 2019 and May 2020 armed groups in Ituri killed at least 531 civilians, 375 of them since March. State forces are also accused of killing 17 civilians during the same time. A Lendu-led militia, the Congo Economic Development Cooperative (CODECO), perpetrated multiple massacres of civilians. In late March, state forces killed Justin Ngudjolo, the leader of CODECO, fracturing the group into multiple splinter groups. Retaliatory attacks by these groups contributed to an escalation in attacks in April and May. Reports indicate Lendu-led militias targeted civilians based on their ethnicity, connected to a struggle for resources and political representation.

A UN report on sexual violence in conflict found that Lendu-led militias targeted Hema women and girls during village massacres in Ituri. State forces—who are stationed in Ituri to protect civilians—are also accused of perpetrating sexual violence against the local population, including attacking women and girls fleeing from violence.

Attacks have severely impacted children in the area. In just April and May of this year, UNICEF recorded over 100 serious child rights violations in Ituri including killings, mutilation, rape, and attacks on schools and health centers. Displacement is another major concern. More than a million people have been displaced from their homes in eastern DRC in the last six months, according to UNHCR. Displaced people have been directly targeted in attacks, as armed groups killed, maimed, and raped villagers while they attempted to flee. Villages and schools hosting displaced people from previous attacks have been looted and burned.

Multiple Epidemics

In the midst of this violence, civilians are faced with myriad risks to their lives. The DRC is facing multiple epidemics simultaneously, including the global COVID-19 pandemic, Ebola, and measles. The government reports more than 8,000 cases of COVID-19 as of July 2020, though cases are likely being undercounted due to limited testing. The head of MONUSCO, the UN’s peacekeeping force in the DRC, reports the COVID-19 pandemic is likely constraining the government’s capacity, already weak, to respond to attacks on civilians by nonstate actors.

Other epidemics are contributing to the strain on government capacity. Ebola remains a significant health risk for the DRC, despite recent successes. In June, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared an end to the world’s second-deadliest outbreak of Ebola located in eastern DRC. Less than a month later, the WHO identified a new Ebola outbreak in western DRC. The country is also facing the world’s largest and fastest moving outbreak of measles.

International Response

Recent reports of violence in Ituri have been met with increasing concern from international institutions. In January, the UN reported that violence in Ituri may constitute “crimes against humanity.” On June 4, the Prosecutor of the ICC issued a warning that the crimes in Ituri might be within the court's jurisdiction, a rare example of the court using its prevention mandate. In late June, the UNHCR spokesperson said they were alarmed by the violence.

Historically efforts from the international community to stop mass atrocities in the DRC have proved insufficient. MONUSCO remains active today, though critics say budget cuts have undercut the mission’s ability to restrain violence in eastern DRC. The international community needs to focus on long term institution building throughout the region, while in the short-term strengthening MONUSCO’s ability to protect civilians.

Conclusion

Ituri is not the only province in eastern DRC that has had recent large-scale violence against civilians. Most notably in North and South Kivu where armed groups have killed hundreds of civilians this year, further constraining state capacity. As violence in Ituri continues to escalate, the crisis calls for immediate intervention from the international forces that are already on the ground who are mandated to protect civilians from harm. In addition, there should be further investigation from UN justice bodies in order to end the impunity and reset the primacy of civilian life in the region. Finally, it is critical that Congolese state forces commit to the protection of civilians and do not perpetrate their own human rights violations in their response to local militias.

View All Blog Posts