October 16, 2020

By Tyler Jager, Program Intern

On June 29, 2020, Hachalu Hundessa, a popular Ethiopian musician and Oromo activist, was shot and killed outside his home in Addis Ababa. The announcement of the 34-year-old’s death sparked days of demonstrations in the capital, with thousands flooding the streets, calling for justice. Ethiopian security forces responded violently to the protests, killing or injuring dozens of activists and arresting opposition politicians, dissidents, and journalists.

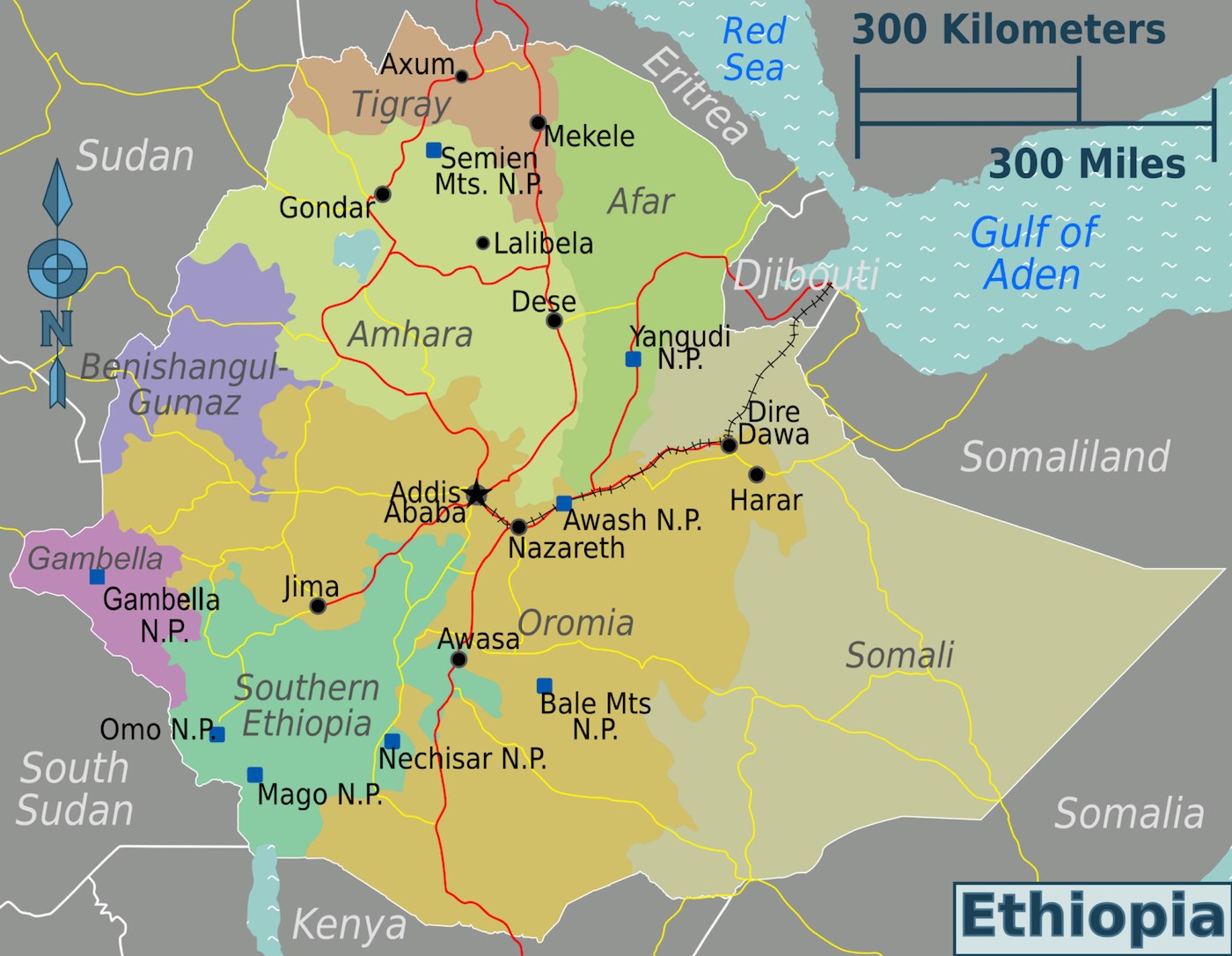

Alongside state violence, armed youth mobs targeted Amhara and Oromo households for killing and property destruction. In August, Ethiopia’s Tigray region announced it would subvert national leadership and hold regional elections. The chair of the African Union Commission and UN independent monitors have urged authorities to protect peaceful demonstrations, and cautioned citizens against committing acts of violence.

The Simon-Skjodt Center has identified a growing risk of mass killing in Ethiopia. In the Early Warning Project’s Statistical Risk Assessment of 2019-2020, Ethiopia was ranked as the 10th most likely country to experience a mass killing, rising from 32nd place in the previous 2018-2019 assessment. This rise in rank accompanies an uptick of inter-communal violence and unrest in the country, where more than two million people are displaced. General elections in Ethiopia scheduled for August 2020 were delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and human rights groups are concerned that recent unrest could accelerate political tensions in Addis Ababa.

Protests, Repression, and Inter-communal Violence

For many Oromo people in Ethiopia, the activist and singer Hachalu Hundessa was a source of hope and affirmation. During protests that swept the country from 2015 to 2018, Hundeessaa’s music was unabashedly political. He and other musicians provided a powerful soundtrack for a national movement led by youth, farmers and activist groups to address long-held grievances over brutal anti-Oromo suppression. His assassination was met with widespread grief and anger from the Oromo community, expressed through social media and mass demonstrations throughout the Oromia region.

Amid the protests, state security forces and armed mobs killed over 239 people, many of them protestors, dissidents, and members of targeted ethnic communities. Starting in June, state military and police began to use deadly force against primarily Oromo demonstrators, and detained thousands more, including figures such as Jawar Mohammed, an Oromo opposition leader widely followed on social media, and Eskinder Nega, formerly imprisoned journalist and critic of the Abiy administration. An internet shutdown, imposed by the central government in June and lifted in late July, severely limited the flow of information from affected regions.

The police have also failed to protect residents from local inter-communal violence. Groups of young Oromo men reportedly targeted Amhara people and other ethnic and religious minorities in vigilante attacks, burning homes and roaming neighborhoods with machetes and clubs. Other Oromo residents, horrified by bloodshed that runs counter to decades of peaceful coexistence in local communities, offered protection to their Amhara neighbors, sheltering them in their homes, schools, and places of worship. The attacks and destruction have displaced over 10,000 people to other regions, where they are vulnerable to spontaneous violence and food insecurity.

Long-standing Grievances, Renewed Abuses

Hachalu’s murder in June was a reminder of the historic persecution that the Oromo have faced from the central government. Ever since the rule of Haile Selassie, historic grievances from inequality, violence and neglect have motivated Oromo political hopes for greater autonomy.

At first, many Oromo leaders embraced the pan-Ethiopian federalist vision of the current ruling coalition, the Prosperity Party, formerly known as the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF). The Prosperity Party supports a more centralized national government and includes political elites from each of Ethiopia’s major ethnic groups. However, other parties have offered nationalist or even secessionist visions of Oromo autonomy in Ethiopia, particularly the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF), whose armed wing was allowed to return to Ethiopia last year after exile. The Oromo opposition coalition supports a modern version of this ideal, seeing itself as the true torchbearer of federalism and regional autonomy.

President Abiy Ahmed is a member of the Prosperity Party, a Nobel Peace Prize winner, and the country’s first Oromo leader. But despite his election on a platform of liberal, pluralistic reform, many Oromo leaders have been dissatisfied with Abiy’s leadership. In its first year, the administration freed political prisoners, welcomed exiles, and began peace negotiations with Eritrea after two decades of conflict. More recently, however, the government adopted repressive tactics resembling the authoritarianism of previous regimes. In 2018, the Ethopian army committed “horrendous human rights abuses” including rape and extrajudicial killings in a brutal counterinsurgency against the separatist OLF, according to a recent Amnesty International report. The uprising of the past two months has parallels to the military abuses, civil unrest, and internet shutdowns of 2018-19.

Current Risks

The multiple conflicts currently roiling Ethiopia and the willingness of antagonists to use violence against civilian populations indicates a risk of further atrocities. As more separatist actors and armed groups take advantage of unrest spreading to further regions of Ethiopia, state security could again target civilians. Leaders in the Tigray region have already defied the central government by conducting regional elections in advance of the delayed national elections, now slated for 2021. The armed youth-led mobs who targeted and killed Oromo and Amhara community members in July have not faced justice. Resentment directed at the Abiy administration from the Oromo opposition is only growing.

States can use an atrocity prevention framework to recognize escalating steps toward mass killings and take measures to address atrocity risk factors. Foreign governments and human rights organizations should follow the lead of the African Union to support peace processes between the central government and regional groups and condemn violence against civilians. Finally, observers can draw from the work of Ethiopian journalists and watchdog groups, who continue to monitor violence against civilians.

Tyler Jager is the Program Intern at the Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide, and a student at Yale University.

View All Blog Posts