< About the Museum

Architecture and Art

Architecture

In designing the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the late architect James Ingo Freed, of Pei Cobb Freed & Partners, visited a number of historical Holocaust sites, including several camps and ghettos, to examine their structures and materials. The Museum he built as a result is not a neutral shell. Instead, the architecture—through a collection of abstract forms both invented and drawn from memory—alludes to the history the Museum addresses.

“There are no literal references to particular places or occurrences from the historic event,” he explained. “Instead, the architectural form is open-ended so the Museum becomes a resonator of memory.”

-

Exterior

The Museum's exterior looks simple at first, but its architecture is symbolic of the troubling history of the Holocaust.

-

Hall of Witness

The building employs construction methods from the industrial past, and old-fashioned techniques are clearly visible in the Hall of Witness.

-

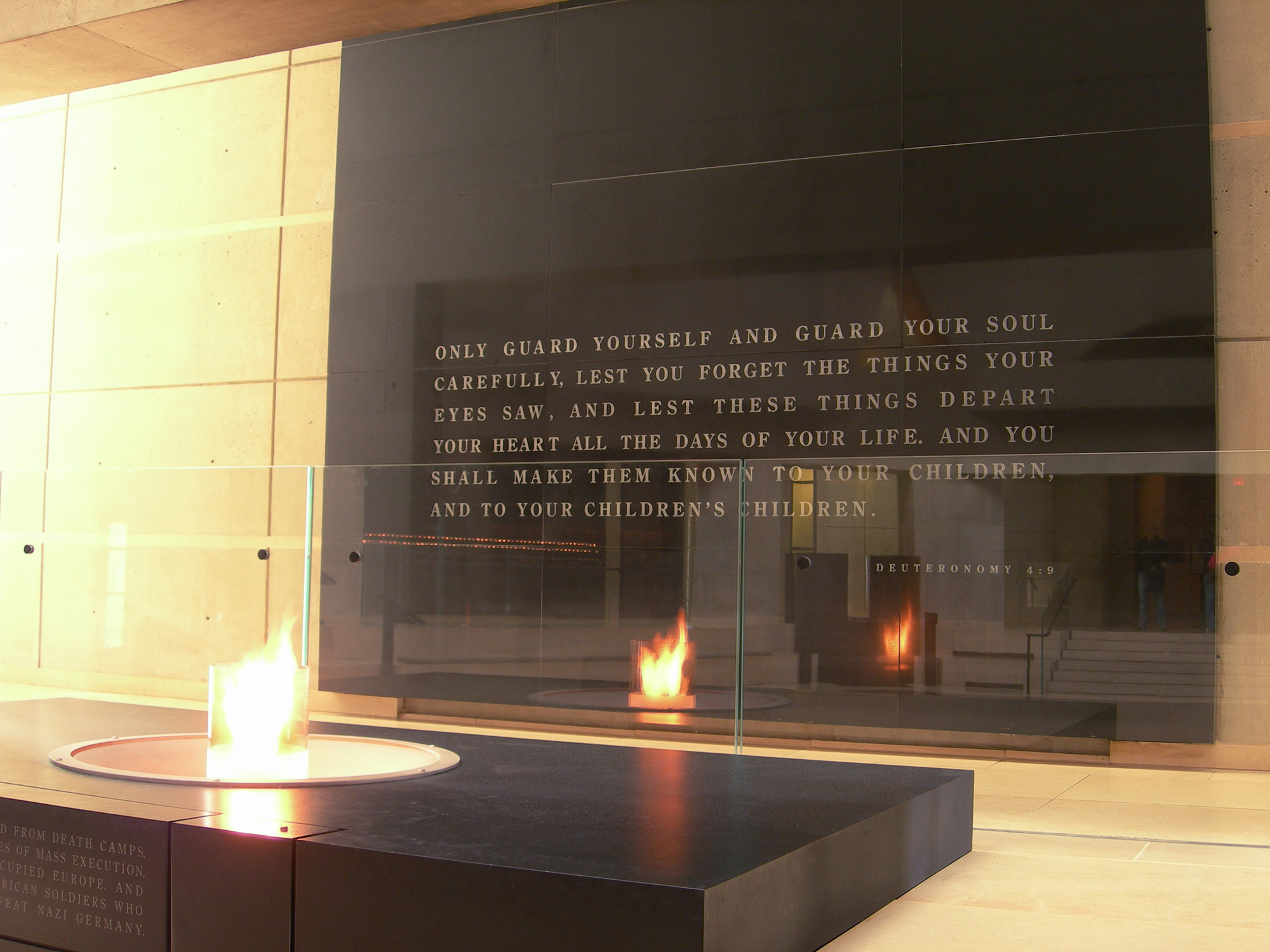

Hall of Remembrance

Situated in the hexagonal structure that overlooks Eisenhower Plaza, the Hall of Remembrance is a simple, solemn space designed for public ceremonies and individual reflection.

Art

The Museum’s four site-specific works of art were commissioned and chosen by an independent jury, and Museum architect James Ingo Freed collaborated with each of the artists to ensure a harmonious relationship between their work and its context. Just as the architecture of the building draws much of its power from the history of the Holocaust, the four works of art, displayed in and outside the building, evoke emotion and reinforce the Museum’s memorial function.

-

Consequence

Sol LeWitt’s wall drawing Consequence, is located in the Museum’s second-floor lounge.

-

Gravity

Richard Serra’s monolithic sculpture Gravity is wedged near the black granite wall at the bottom of the stairs in the southwest corner of the Hall of Witness.

-

Loss and Regeneration

Joel Shapiro’s Loss and Regeneration is located on the Museum's plaza along Raoul Wallenberg Place.

-

Memorial

Ellsworth Kelly’s four white wall sculptures, collectively titled Memorial, are situated in the Museum’s light-filled third-floor lounge.