Located on the first floor, the Hall of Witness is a three-story, sky-lit gathering place. The elements of dislocation first introduced outside the building reappear here. Visitors who arrive from 14th Street move through a canopied entrance and cross over a raw steel platform into the Hall. It is a transitional threshold, separating and displacing the visitor from the outside world.

The Architectural "Language"

The building employs construction methods from the industrial past, and old-fashioned techniques are clearly visible in the Hall of Witness: steel plates, bolted metal, rivets. The raw brick is load-bearing, turnbuckles connect tie rods, and structure is exposed. This architectural “language” is an ironic criticism of early modernism’s lofty ideals of reason and order that were perverted to build the factories of death.

Overhead, a skewed and twisted skylight lets sheets of unfiltered but fragmented light pass through a tensioned ribbing of heavy steel trusses. The glass roof shears the building on a diagonal line. The skylight drops beneath the flanking brick walls to the third-floor level, pressing down on the open space below even as it opens the visitor’s view to the sky above. It is warped, deformed, and eccentrically pitched. The effect is to, architect James Ingo Freed said, “tell the visitor something is amiss here.”

Above the skylight, visitors in the Hall can see spectral-like figures crossing overhead on glass bridges that connect the north and south towers, lending an unsettling air of surveillance. On the floor of the Hall of Witness, a glass-block incision cuts the granite in a rift that echoes the axis of the skylight above.

The fissure underscores a sense of imbalance, distortion, and rupture—characteristics of the society in which the Holocaust took place. Along the north side of the Hall, the floor abruptly stops five feet away from the wall, leaving a deep gap to be crossed by a bridge and to funnel light into the lower level below.

The Hall of Witness —US Holocaust Memorial Museum

Summoning the Themes of the Holocaust

Design features that fill the Hall of Witness and recur throughout the building summon more directly the tragic themes of the Holocaust. Crisscrossed steel trappings seem to brace the harsh brick walls against some great internal pressure. Inverted triangular shapes repeat in windows, floors, walls, and ceilings. The Hall’s main staircase narrows unnaturally toward the top, like receding rail tracks heading to a camp. Exposed beams, arched brick entryways, boarded windows, metal railings, steel gates, fences, bridges, barriers, and screens all “impound” the visitor and send disturbing signals of separation.

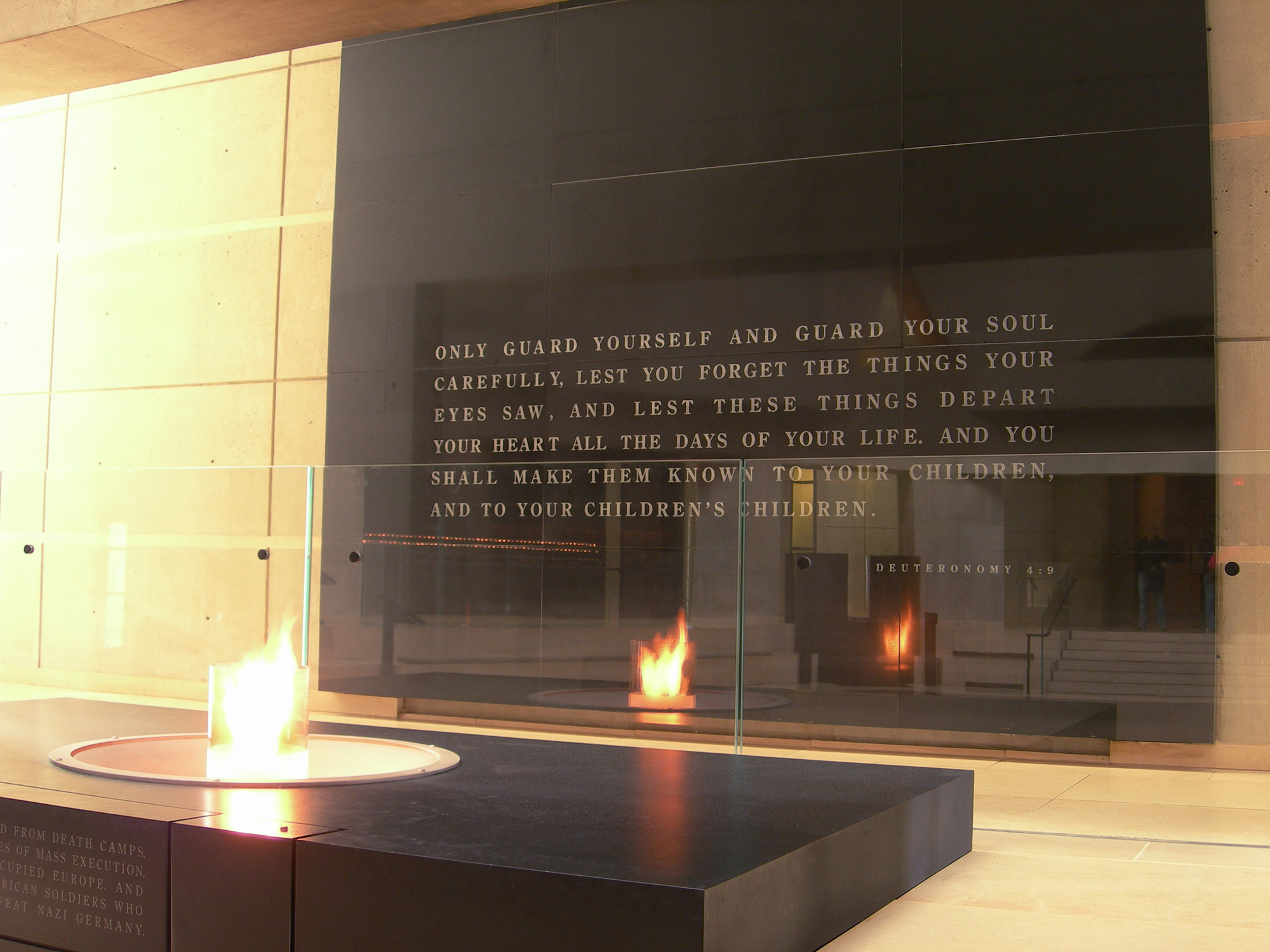

Everywhere there are dualities and options. The west wall of the Hall of Witness is made of black granite, the east wall of white marble—the former ominous, the latter hopeful. The play of light and shadow, along with contrasting wide and narrow spaces, evokes contradictory notions of accessibility and confinement.

The Hall of Witness is defined by unpredictability and uncertainty. Altogether, the interior suggests a departure from the norm, informing visitors they are in a profoundly different place. It is an environment that stimulates memory and sets an emotional stage for the Museum’s exhibitions.