Methodist Bishop Edwin H. HughesClose

Washington, DC. November 15, 1938. —National Archives and Records Administration (NARA)

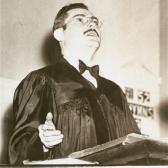

Reverend R. I. Gannon of Fordham UniversityClose

Washington, DC. November 15, 1938. —National Archives and Records Administration (NARA)

22,000 Jam Garden in Protest Against Nazi PersecutionsClose

New York, NY. November 21, 1938. —National Archives and Records Administration (NARA)

The November 9, 1938, pogroms sparked a wave of outrage among US religious leaders. In the weeks following, there were numerous editorials, radio broadcasts, and sermons. In a few cases—like the historic Church of the Pilgrimage in Plymouth, Massachusetts—local Christian clergy invited their Jewish colleagues to address their congregations for the first time. While the prevalence of such striking examples of interfaith solidarity should not be overestimated, they do reflect a growing level of awareness among US Christians about what was happening in Nazi Germany. That awareness was strengthened by some of the most prominent Catholic and Protestant publications of that era, such as America magazine and the Christian Century, which regularly reported on events in Nazi Germany.

Rabbi Samuel A. Friedman of Beth Jacob Synagogue speaks from the pulpit of the Church of the Pilgrimage. US Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Corbis-Bettmann

These reports, and the reactions of church leaders, were very much shaped by the concerns of US religious leaders about what was happening in this country. The 1930s saw a dramatic increase in the number of antisemitic groups in the United States—from five in 1932 to 120 in 1939, according to a 1941 report by the American Council on Public Affairs. The largest of these, the German-American Bund, openly disseminated Nazi propaganda.

The most prominent antisemitic figure of that era was Fr. Charles Coughlin, a Canadian-born Catholic priest who was assigned to a parish in Michigan. Antisemitic, anti-Communist, and isolationist, Coughlin aligned himself with the Christian Front, a radical group shut down by the FBI in 1940 after its plans for violent attacks against several members of Congress were uncovered. At the peak of his popularity in the mid-1930s, Coughlin’s weekly radio broadcasts drew an audience of around 3.5 million listeners and his publication, Social Justice, had one million subscribers. Coughlin’s response to Kristallnacht was to claim that “Jewish persecution only followed after Christians first were persecuted.” Following this, some radio stations began to refuse to broadcast his program.

The mainstream church leadership viewed the rise of antisemitic hate groups here and the developments in Nazi Germany as part of a larger threat to democratic values, and this was the tone in which they responded to the violence in Nazi Germany. This approach can be seen in their statements about Kristallnacht:

- Some of the statements clearly recognized and focused on the immediate threat to Germany’s Jews. Others framed the events of Kristallnacht in a much larger litany of generalized religious persecution.

- Many of the statements framed the violence in Germany, and the growing divisions in the United States, as a general threat to the larger democratic ideals of this country.

- Catholics in particular were concerned with anti-Catholic prejudices and the unfolding Spanish Civil War, in which thousands of Catholic clergy and laypeople had been killed by the anti-clerical Republican movement. US Catholic attitudes toward Nazi Germany (external link) were complicated by the fact that the pro-Catholic Spanish Nationalist movement was supported by both Nazi Germany and fascist Italy.

- Finally, the church leaders’ condemnation of Nazi persecution of Jews was framed in two primary ways. It was often described as a form of racial persecution, but many of the statements also framed it as a form of generalized anti-religious persecution that would eventually touch Christians as well. Hence many statements warned that the violence against the Jews was a mere prelude to violence against Christians in Germany.

A nationwide broadcast under the auspices of the Catholic University of America in Washington, DC, was broadcast by the CBS and NBC radio networks on Wednesday, November 16, 1938.

Some of these elements are reflected in the statement issued by the Federal Council of Churches (FCC), a national Protestant organization that included 33 member churches. Following Kristallnacht, the FCC declared November 20, 1938, to be a “national day of prayer” for the “victims of racial and religious oppression,” saying:

“This inhumane treatment falls heavily on many groups in many lands …We would direct special attention, however, to the plight of those of Jewish blood in Europe, whether Jewish or Christian in faith …The Jews of the world have been most generous in affording help to their own people and in countless instances have given assistance to Christians of Jewish blood. But we have no right to expect them to do this …We plead also for a united effort on the part of all the people of God to combat the hateful anti-Semitism which prevails in many lands and even in our own country … In the words of the Oxford Conference on Church, Community and State: “Racial pride and exploitation of other races is sin. Against these the Christian Church the world over must set its face implacably.”

Did these reactions lead to action? Since 1933, the focus of most US church leaders concerned about Nazi Germany had been refugee work, but here the churches lagged sadly behind Jewish organizations in staffing, support, and financial assistance. Moreover, their emphasis was always on assisting refugees who were Christian. Following Kristallnacht, however, there was a brief resurgence of activism by a few Christian leaders—particularly Henry Leiper and Charles Macfarland of the Federal Council of Churches, who joined Jewish colleagues in lobbying for changes in immigration law. Such activism, it must be said, came from only a few prominent ecumenical and church leaders, and didn’t seem to find much of an echo among ordinary church members. Once the war began, religious refugee work was moved to the sidelines.

The religious reactions to Kristallnacht show an awareness of what was happening that would shape subsequent church statements as the Holocaust unfolded and eventually led some denominations—such as the Presbyterians in May 1939—to condemn antisemitism explicitly.