Students have questions while learning about the Holocaust. These short answers are meant to help educators address these questions. This page includes additional resources for educators and students, labeled with Teach and Learn.

- Teach: Explore lesson plans and educational resources for Educators.

- Learn: Read articles on the people, places, and events of the Holocaust in the Holocaust Encyclopedia.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What was the Holocaust?

- Why the Jews?

- What caused the Holocaust?

- When did the Holocaust happen?

- Who were the Nazis?

- Did Hitler brainwash the Germans? Why did so many people go along with his plans?

- How did the Nazis know who was Jewish?

- Did Hitler have Jewish relatives?

- Why didn’t the Jews just leave?

- Why didn’t the Jews fight back?

- Was the Holocaust a secret?

- Did the Nazis only go after Jews or other people too?

- Did Americans know about the Holocaust and what did they do?

- How did the Holocaust end?

- How do we know how many people died in the Holocaust?

- What happened to the Nazis after the Holocaust?

- What does the word Holocaust mean?

- Why do we study the Holocaust?

What was the Holocaust?

The Museum’s guidelines for teaching about the Holocaust recommend educators define the term “Holocaust” for students.

The Holocaust was the systematic, state-sponsored, persecution and murder of six million Jews by the Nazi regime and its collaborators between 1933 and 1945 across Europe and North Africa. The height of the persecution and murder occurred during World War II. By the end of the war in 1945, the Germans and their collaborators had killed nearly two out of every three European Jews.

The Nazis believed that Germans were racially superior. They believed Jews were a threat to the so-called German racial community. While Jews were the primary victims, the Nazis also targeted other groups for persecution and murder. The Nazis claimed that Roma, people with disabilities, some Slavic peoples (especially Poles and Russians), and Black people were biologically inferior.

The regime persecuted other groups because of politics, ideology, or behavior. These groups included Communists, Socialists, Jehovah’s Witnesses, gay men, and people the Nazis called “asocials” and “professional criminals.”

- Teach: The Museum’s timeline activity allows students to read about the experiences of people targeted by the Nazi regime.

- Learn: Read the “Introduction to the Holocaust” in the Holocaust Encyclopedia.

Why the Jews?

Antisemitism, the fear or hatred of Jews, existed in Europe for centuries before the Holocaust. The early Christian church portrayed Jews as unwilling to accept the word of God, as agents of the devil, and as murderers of Jesus. (The Vatican renounced these accusations in the 1960s.)

During the Middle Ages, laws restricted Jews and prevented them from owning land or holding public office. Jews were excluded from most occupations. This forced them to make a living through money-lending, trade, and commerce. Jews were accused of causing plagues, of murdering children for religious rituals, and of secretly conspiring to dominate the world. None of these accusations were true.

A new kind of antisemitism emerged in the second half of the 19th century. At its core was the theory that Jews were not merely a religious group but a separate “race.” Antisemites believed Jews were dangerous and threatening because of their “Jewish blood.” They believed that Jews would still be a threat even if a Jewish person converted to Christianity. Antisemitic racism united these new racial theories with older anti-Jewish stereotypes. These ideas gained wide acceptance.

After World War I, the new Nazi Party and its leader, Adolf Hitler, blamed Jews for Germany’s defeat. They claimed that German Jews, a small minority of Germany’s population, had “stabbed Germany in the back.” This was untrue—German Jews fought and died for Germany during the war. Historians cannot trace Hitler’s antisemitism to any specific event or incident. When the Nazi Party took power in Germany in 1933, their antisemitic racism became official government policy.

- Teach: Educators can use the History of Antisemitism and the Holocaust and Nazi Racism lesson plans to explore this question with students. It is important to emphasize that Jews were not to blame for the Holocaust, and did not do anything to “cause” antisemitism.

- Learn: Read “Antisemitism” in the Holocaust Enyclopedia.

What caused the Holocaust?

The Holocaust was caused by many factors, including millions of individual decisions made by ordinary people who chose to actively participate in—or at least tolerate—the persecution and murder of their neighbors.

- Teach: Educators can use The Path to Nazi Genocide, a 37-minute Museum-produced film to help students explore the causes of the Holocaust. It is available in multiple languages and includes a worksheet.

- Learn: Read “What Conditions, Ideologies, and Ideas Made the Holocaust Possible?” in the Holocaust Encyclopedia.

The following factors contributed to the Holocaust:

Racial Antisemitism

Antisemitism, the fear or hatred of Jews, existed in Europe for centuries before the Holocaust. In the late 19th century, eugenics became popular. Eugenics was the theory that humans can be categorized in specific races. Each “race” had its own unchangeable traits. Some “races” were biologically, culturally, and morally superior to others. Eugenics has now been proven false.

The Nazis promoted racial antisemitism. It did not matter whether a person practiced the Jewish faith. The Nazis believed Jews belonged to a separate race and had distinct “Jewish blood.” This belief was false: there is no biological difference between Jews and non-Jews. The Nazis attributed many negative stereotypes to Jews and “Jewish” behavior. The Nazis saw Jews as the source of all evil: disease, social injustice, cultural decline, capitalism, and communism.

- Teach: Educators can use the History of Antisemitism and the Holocaust lesson plan to explore these concepts with students.

Political Instability

Many Germans were willing to tolerate Nazi antisemitism. Germany suffered a humiliating defeat in World War I (1914–1918). Many believed the Nazi Party was restoring Germany’s status as a world power. The Nazis also promised to restore Germany’s economy. They vowed to end political instability and violence.

Hitler was a strong and popular leader. He blamed Jews for all of Germany’s problems. The Nazi regime economically, politically, and socially marginalized the Jewish community. They tried to force Jews to leave German territory. German Jews made up less than one percent of Germany’s population. The Nazi regime was able to marginalize such a small community with virtually no public protest.

War

In defiance of the Treaty of Versailles, Germany remilitarized and prepared for war. The United States and other countries, still suffering under the Great Depression and remembering the horror of World War I, did not meaningfully intervene to protest until Germany invaded Poland in 1939.

Even then, the United States remained neutral in World War II until December 1941. It prioritized the defeat of Nazi Germany over the rescue of Jews.

During World War II, as the German military invaded and conquered territories, millions of European Jews came under Nazi control. Nazi policy moved from forced emigration to mass murder. By 1945, when the Allied nations defeated Germany in World War II, the Nazis and their collaborators had murdered six million European Jews.

- Learn: Read “What Does War Make Possible?” in the Holocaust Encyclopedia.

Collaboration

The Holocaust could not have happened without the active or passive participation of millions of people. Some people recognized that they could personally benefit from the persecution and murder of Jews. They acquired the property or homes of Jews who were deported and murdered. Some took over the businesses of Jews forced to emigrate or sent to concentration camps. Other people found jobs in the Nazi regime. These jobs gave them money, political power, and influence. In countries that Germany invaded, many collaborators saw the benefit of assisting their new leaders. They chose to denounce their Jewish neighbors.

- Teach: Educators can download a poster set related to the Museum’s exhibition Some Were Neighbors: Collaboration and Complicity in the Holocaust to explore these themes in your classroom. The poster set is available in multiple languages.

Propaganda and Societal Pressure

There was a great deal of pressure to conform. Even if people were not antisemitic to begin with, Nazi leaders and propaganda urged people to hate Jews. Nazi ideas about “race” and the supposed inferiority of Jews were taught in schools. The government arrested political opponents or members of the press who criticized Hitler or the Nazi Party. They were put in jails and concentration camps. Few people were brave enough to publicly speak out or to help Jews, especially when they could be arrested or killed for doing so.

- Teach: Explore lesson plans related to Nazi propaganda—including a meme analysis lesson.

When did the Holocaust happen?

The Holocaust was the systematic, state-sponsored, persecution and murder of six million Jews by the Nazi regime and its collaborators between 1933 and 1945. In January 1933, Adolf Hitler, the leader of the Nazi Party, was appointed the chancellor of Germany. The Nazi Party quickly turned Germany from a weak new democracy into a one-party dictatorship. It began persecuting German Jews almost immediately. By 1935, Jews were stripped of their German citizenship. In 1938, Jewish men began to be arrested and sent to concentration camps just for being Jewish.

Nazi Germany also annexed, invaded, and occupied neighboring countries to obtain what they called Lebensraum (living space). In September 1939, the German invasion of Poland led Great Britain and France to declare war, and World War II began. As Germany’s territory grew, millions of Jews came under Nazi control. German authorities rounded up Jews and forced many of them into ghettos.

By the summer of 1941, Nazi Germany and its collaborators began to systematically murder European Jews. The Nazis referred to this plan as the “Final Solution.” Sometimes Jews were killed outright—entire villages rounded up and shot, or murdered in killing centers. In other areas, Jews were forced to labor for the German war effort until they died of overwork or starvation.

The Allies defeated Nazi Germany in World War II in May 1945. By that time, the Nazis and their collaborators had murdered approximately six million Jews.

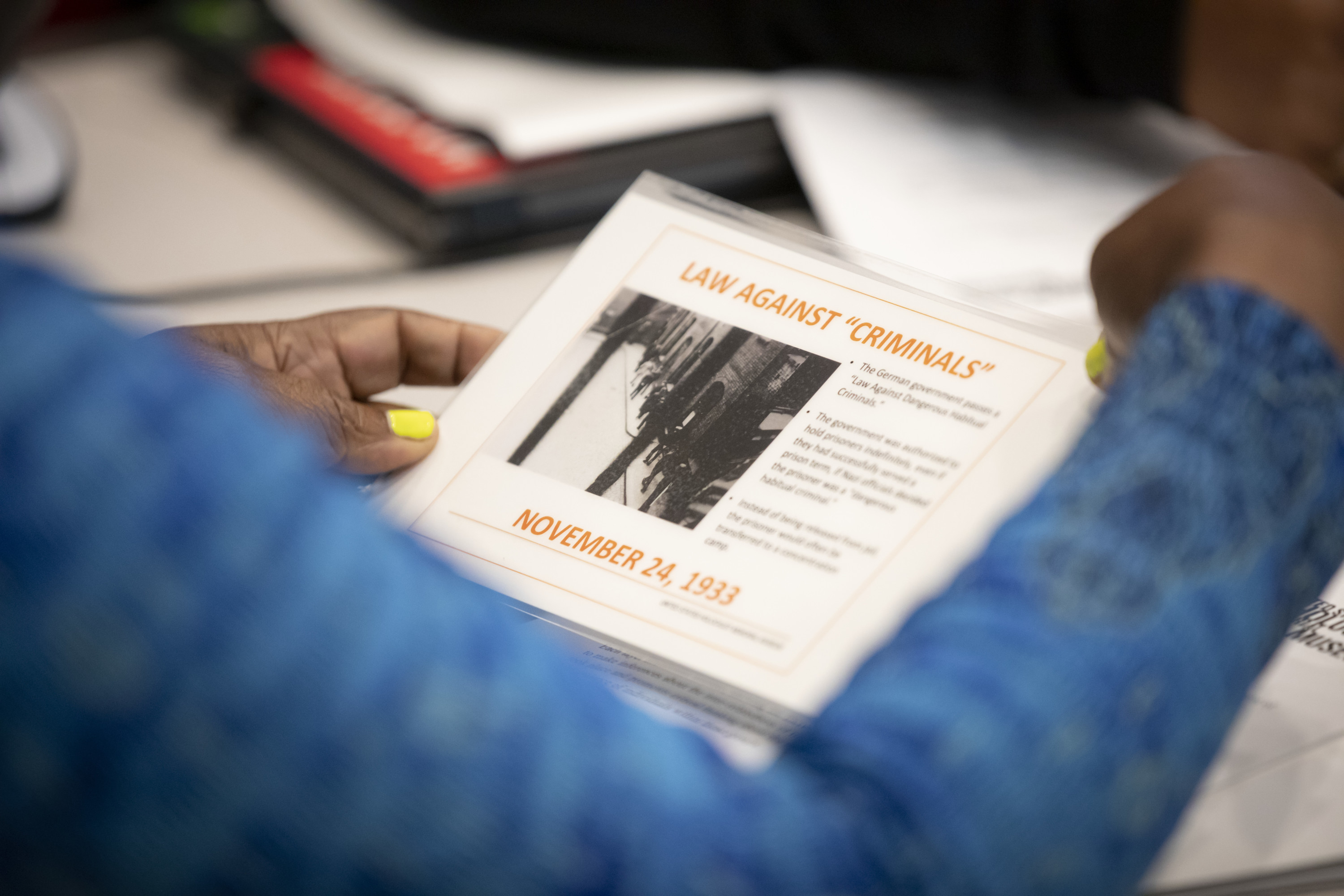

- Teach: The Museum’s timeline activity allows students to explore Nazi laws and decrees, as well as important events related to the Holocaust. The timeline also includes profile cards for individuals targeted by the Nazi regime. Educators can request a free set of timeline cards here.

Not sure where to begin?

Museum educators can connect you with classroom resources and answer questions about teaching the Holocaust.

Who were the Nazis?

The National Socialist German Workers’ Party—also known as the Nazi Party—was a far-right racist and antisemitic political party. The Nazi Party was founded in 1920. It sought to lure German workers away from socialism and communism and commit them to its antisemitic and anti-Marxist ideology. Adolf Hitler became the Führer (or Leader) of the Nazi Party and turned it into a mass movement. The Nazi Party grew steadily under Hitler’s leadership. It attracted support from influential people in the military, big business, and society. It absorbed other radical right-wing groups.

The Nazis attracted attention and interest by using propaganda. The Party staged many meetings, parades, and rallies. It created stirring slogans that appeared in the press and on posters. It displayed eye-catching emblems and uniforms. In addition, it created auxiliary organizations to appeal to specific groups. For example, there were groups for youth, women, teachers, and doctors. The Nazi Party became especially popular with German youth and university students.

- Teach: Explore lesson plans related to Nazi propaganda, including a meme analysis lesson.

Political instability in Germany after World War I meant that Germany was a weak new democracy. Other politicians thought they could control Hitler and his followers. The Nazis used emergency decrees, violence, and intimidation to quickly seize control. The Nazis abolished all other political parties and ruled the country as a one-party, totalitarian dictatorship from 1933 to 1945. The Party used its power to persecute Jews. It controlled all aspects of German life. The Nazis waged a war of territorial conquest in Europe from 1939-1945 (World War II). During that time, it also carried out a genocide now known as the Holocaust. The Nazis’ power only ended when Germany lost World War II.

Did Hitler brainwash the Germans? Why did so many people go along with his plans?

Hitler and other Nazi Party leaders played a central role in the Holocaust. Nazi propaganda demonized Jews, but the German people were not brainwashed, nor were any of the Nazis’ collaborators. In countries across Europe, tens of thousands of ordinary people actively collaborated with German perpetrators of the Holocaust, each for their own reasons. Many more supported or tolerated the crimes. Millions of ordinary people witnessed the crimes of the Holocaust—in the countryside and city squares, in stores and schools, in homes and workplaces. The Holocaust happened because of millions of individual choices.

- Teach: The Museum’s four-day Overview of the Holocaust lesson plan encourages students to explore Holocaust history with a special emphasis on the role of ordinary people.

Some people were motivated by antisemitism—the hatred of Jews—or at least tolerated their neighbors’ antisemitism. As early as the Middle Ages, religious hatred led to anti-Jewish legislation, expulsions, and violence. In much of Europe, government policies, customs, and laws segregated Jews from the rest of the population. They were only allowed to perform specific jobs and were prohibited from owning land. In the century prior to the Holocaust, life for Jews improved in many parts of Europe, but these prejudices remained. When the Nazi Party came to power in Germany in 1933, many Germans tolerated Nazi antisemitic policies because they supported Nazi economic improvements. Hitler was a strong and popular leader, and many Germans believed the Nazi Party was restoring Germany’s status as an international power after its humiliating defeat in World War I (1914–1918).

Some people recognized that they could personally benefit from the persecution and murder of Jews. They acquired the property or homes of Jews who were deported and murdered. Some took over the businesses of Jews forced to emigrate or sent to concentration camps. Other people found jobs in the Nazi regime. These jobs gave them money, political power, and influence. In countries that Germany invaded, many collaborators saw the benefit of assisting their new leaders. They chose to denounce their Jewish neighbors.

There was a great deal of pressure to conform. Even if people were not antisemitic to begin with, Nazi leaders and propaganda urged people to hate Jews. Nazi ideas about “race” and the supposed inferiority of Jews were taught in schools. The government arrested political opponents or members of the press who criticized Hitler or the Nazi Party. They were put in jails and concentration camps. Few people were brave enough to publicly speak out or to help Jews, especially when they could be arrested or killed for doing so.

- Teach: Educators can explore lesson plans related to Nazi propaganda, including a meme analysis lesson.

How did the Nazis know who was Jewish?

The Nazis considered Jews to be a separate race with dangerous “Jewish blood.” Since the Nazis believed in a biological difference between Jews and Germans, Jews could not just convert to Christianity to escape Nazi persecution. The Germans and their collaborators used paper records and local knowledge to identify Jews to be rounded up or killed. These records included Jewish community member lists, parish records of Protestant and Catholic churches (for converted Jews), government tax records, and police records.

In both Germany and occupied countries, Nazi officials required Jews to identify themselves as Jewish. Many complied, fearing the consequences if they refused. Some were forced to wear markings, like stars on their clothing, or to add the new middle names of “Israel” or “Sara” to their identification documents. In many of these countries, local citizens often showed authorities where their Jewish neighbors lived. Some even helped in rounding up Jews.

Jews in hiding lived in constant fear of being identified and denounced to officials by individuals in exchange for money or other rewards. Some Jews in larger cities tried to “pass” as non-Jews, particularly if they had lighter hair or eyes. German propaganda highlighted blonde hair and blue eyes as markers of the superior “Aryan” race. Of course, Hitler and many Nazis leaders did not have blonde hair or blue eyes, but as with all racists, their prejudices were not consistent or logical.

Some Jews openly “hid” with documents identifying them as Christians. This was very dangerous. If they were recognized by someone who knew them, they could be killed. This was especially true for Jewish men. Circumcision is a Jewish ritual, but was uncommon for non-Jews at the time. Jewish men knew they could be physically identified as Jewish.

- Learn: Read the Holocaust Encyclopedia article “Locating the Victims.”

Did Hitler have Jewish relatives?

There is no credible evidence that Hitler had any Jewish ancestors. Hitler’s rivals in the early days of the Nazi Party (1919–1921) spread this rumor, and Hitler refused to talk about his own ancestors. Hitler’s father, Alois, was born to an unwed mother, and historians have not been able to confirm the identity of Alois’s father. However, there is no evidence that Alois’s mother had any contact with anyone who was Jewish.

- Learn: Read “Adolf Hitler: Early Years 1889–1913” in the Holocaust Encyclopedia.

Why didn’t the Jews just leave?

Many students ask this question, and the simple answer is that it was very difficult to leave, and very difficult to find a place to go.

The longer answer is that German Jews were patriotic citizens. More than 10,000 had died fighting for Germany in World War I, and many others were wounded. German Jews received medals for their wartime valor and military service. Many German Jewish families had lived in Germany for centuries and were well assimilated by the early 20th century. At first, Nazi Germany targeted the 525,000 Jews in Germany gradually, attempting to make life so difficult that they would be forced to leave their country. Up until 1938 and the nationwide anti-Jewish violence known as Kristallnacht, many Jews in Germany expected to be able to hold out against Nazi-sponsored persecution. They did not think the Nazi Party would remain in power for very long and hoped for positive change in German politics. Before World War II, few could imagine or predict mass murder.

Those who tried to leave had difficulty finding countries willing to take them in, especially since the Nazi regime did not allow them to take their assets out of the country. Many tried to go to the United States but American immigration law limited the number of immigrants who could enter the country. The ongoing Great Depression meant that Jews attempting to go to the United States or elsewhere had to prove they could financially support themselves. This was very difficult since Jews were being robbed by the Germans before they could leave. Even when a new country could be found, a great deal of time, paperwork, and money was needed to get there. In many cases, these obstacles could not be overcome.

By 1938, however, about 150,000 German Jews had already managed to leave their homeland. But after Germany annexed Austria in March 1938, an additional 185,000 Jews came under Nazi rule. Once Germany invaded and occupied Poland, millions of Jews were suddenly living under Nazi occupation. World War II made travel very difficult, and most countries—including the United States—were unwilling to change their immigration laws, fearing that even Jewish refugees might be Nazi spies. In October 1941, Germany made it illegal for Jews to emigrate from any territory under its control. By then, Nazi policy had changed from forced emigration to mass murder.

- Teach: Educators can utilize the Americans and the Holocaust online exhibition and the Challenges to Escape lesson plan to explore this topic with students.

Why didn’t the Jews fight back?

The idea that Jews did not fight back against the Germans and their allies is false. Jews carried out acts of resistance in every German-occupied country and in the territories of Germany’s Axis partners. Against impossible odds, they resisted in ghettos, concentration camps, and killing centers. There were many factors that made resistance difficult, however, including a lack of weapons and resources, deception, fear, and the overwhelming power of the Germans and their collaborators.

- Teach: View recommendations for classroom activities related to Holocaust-era resistance.

- Learn: Read the Holocaust Encyclopedia article “Jewish Resistance” for more information.

Was the Holocaust a secret?

In Europe, the Holocaust was not a secret. Even though the Nazi government controlled the German press, many Europeans knew that Jews were being rounded up and shot, or deported and murdered. Many individuals actively participated in the stigmatization, isolation, impoverishment, and violence culminating in the mass murder of six million European Jews.

People participated in their roles as clerks and by confiscating Jewish property. Railway and transportation employees participated in deportations. Managers and participants in round-ups and deportations arrested Jews. Informants turned them in to the authorities. Some people perpetrated violence against Jews on their own initiative. Others became killers, participating in the mass shootings of Jews and others in occupied Soviet territories. Thousands of eastern Europeans actively participated in these murders and many more witnessed the crimes.

Many more people were onlookers who witnessed persecution or violence against Jews in Nazi Germany and elsewhere. Most failed to speak out as their neighbors, classmates, and co-workers were isolated and impoverished. Only a small minority publicly expressed their disapproval. A few individuals actively assisted the victims. They purchased food or other supplies that were forbidden to Jews, or provided false papers and warnings about upcoming roundups. Some people stored belongings for Jews in hiding, or even hid Jews themselves. This was very dangerous. If caught, rescuers could be punished by arrest and often execution.

In the United States, Americans had a great deal of information about the persecution and murder of Jews as it was happening. Many Americans, however, did not believe the stories and could not imagine the scale of the violence.

- Learn: Visit the Museum’s History Unfolded newspaper project to learn more about how local newspapers in the United States reported on the Holocaust.

Did the Nazis only go after Jews or other people too?

While Jews were the primary victims, the Nazis also targeted other groups for persecution and murder. The Nazis claimed that Roma, people with disabilities, some Slavic peoples (especially Poles and Russians), and Black people were biologically inferior. The regime persecuted other groups because of politics, ideology, or behavior. These groups included Communists, Socialists, Jehovah’s Witnesses, gay men, and people the Nazis called “asocials” and “professional criminals.”

- Teach: The Museum’s timeline activity provides students with the opportunity to read about the experiences of people targeted by the Nazi regime.

Did Americans know about the Holocaust and what did they do?

The Museum’s History Unfolded newspaper database includes tens of thousands of articles that appeared in American newspapers during the Holocaust. These newspapers reported frequently on Hitler and Nazi Germany throughout the 1930s. Americans read headlines about book burning and about Jews being attacked on the street. They read about the Nuremberg Race laws in 1935, when German Jews were stripped of their German citizenship. The Kristallnacht attacks in November 1938 were front-page news in the United States for weeks. Americans staged protests and rallies in support of German Jews. They also sent petitions to the US government calling for action. These protests never became a sustained movement. Most Americans were still not in favor of allowing more immigrants into the United States, particularly if the immigrants were Jewish.

It was very difficult to immigrate to the United States. In 1924, the US Congress passed the Johnson-Reed Act. The law set limits on the maximum number of immigrant visas that could be issued per year to people born in each country. These quotas were designed to limit the immigration of people considered “racially undesirable.” That included southern and eastern European Jews. Unlike today, the United States had no refugee policy. Jews could not come as asylum seekers or migrants. Approximately 180,000-220,000 European Jews immigrated to the United States between 1933-1945, most of them between 1938-1941.

- Teach: The Museum’s Challenges of Escape lesson plan can help you explore this topic in your classroom.

The US Government learned about the systematic killing of Jews almost as soon as it began in the Soviet Union in 1941. In late November 1942, just weeks after American and British troops began to battle the Germans and their allies in North Africa, newspapers reported that two million Jews already had been murdered as part of the Nazi regime’s annihilation plan. In response, the United States and eleven other Allied countries issued a stern declaration vowing to punish the perpetrators of this “bestial policy of cold-blooded extermination” after the war had been won. Yet saving Jews and others targeted for murder by the Nazi regime and its collaborators never became a priority.

As more information about Nazi mass murder reached the United States, public protests and protests within the Roosevelt administration led President Roosevelt to create the War Refugee Board in January 1944. The establishment of the War Refugee Board marked the first time the US government adopted a policy of trying to rescue victims of Nazi persecution. The War Refugee Board coordinated the work of both US and international refugee aid organizations, sending millions of dollars into German-occupied Europe for relief and rescue. The War Refugee Board also recommended to the War Department that the US military bomb the gas chambers at Auschwitz Birkenau. The War Department responded that it was not a military priority. The War Refugee Board’s final report estimated that it rescued “tens of thousands” of people and assisted “hundreds of thousands” more.

The US military fought for almost four years to defend democracy during World War II. More than 400,000 Americans died in the war. The American people—soldiers and civilians alike—made enormous sacrifices to free Europe from Nazi oppression. The United States could have done more to publicize information about Nazi atrocities, to pressure the other Allies and neutral nations to help endangered Jews, and to support resistance groups against the Nazis. Prior to the war, the US government could have enlarged or filled its immigration quotas to allow more Jewish refugees to enter the country. These acts together might have reduced the death toll, but they would not have prevented the Holocaust.

- Teach: The Museum has many classroom resources to address what Americans knew and did during the Holocaust. Teachers can explore the Americans and the Holocaust online exhibition and choose from numerous lesson plans related to American responses to the Holocaust.

How did the Holocaust end?

The Holocaust ended in May 1945. It ended with the military defeat of Nazi Germany and its European collaborators in World War II. Although the liberation of Nazi camps was not a primary objective of the Allied military campaign, Soviet, US, British, and Canadian troops freed prisoners from their SS guards. They provided them with food and badly needed medical support and collected evidence for war crimes trials.

Holocaust Encyclopedia

Explore our comprehensive entries on the events, people, and places of the Holocaust.

How do we know how many people died in the Holocaust?

The Holocaust is the best documented case of genocide. Despite this, calculating the exact numbers of individuals who were killed as the result of Nazi policies is an impossible task. There is no single wartime document that spells out how many people were killed.

Historians estimate that approximately six million Jews were murdered during the Holocaust. This includes approximately 2.5 million in killing centers, two million in mass shooting operations, and more than 800,000 in ghettos. Although the Holocaust specifically refers to the murder of European Jews, Nazi Germany and its collaborators also killed non-Jews. They killed seven million Soviet citizens, three million Soviet prisoners of war, 1.8 million non-Jewish Polish civilians, between 250,000–500,000 Roma, and 250,000 people with physical and mental disabilities.

- Learn: Read “Documenting the Number of Victims of Nazi Persecution” in the Holocaust Encyclopedia.

What happened to the Nazis after the Holocaust?

Beginning in the winter of 1942, the governments of the Allied powers announced their intent to punish Nazi war criminals. In August 1945, three months after the end of World War II, France, the Soviet Union, Great Britain, and the United States created an International Military Tribunal (IMT) to put German leaders on trial. After much debate, 24 defendants were chosen to represent a cross-section of Nazi diplomatic, economic, political, and military leadership. Adolf Hitler, Heinrich Himmler, and Joseph Goebbels could not be tried because they committed suicide at the end of the war or soon afterwards.

The trial began on November 20, 1945, in the Palace of Justice in Nuremberg, Germany. The Nazi defendants were indicted on four charges:

- Conspiracy to commit crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity;

- Crimes against peace;

- War crimes; and

- Crimes against humanity.

The Holocaust was not the main focus of the trial, but prosecutors presented considerable evidence about the “Final Solution,” the Nazi plan to exterminate the Jewish people. This information included the mass murder operations at Auschwitz, the destruction of the Warsaw ghetto, and the estimate of six million Jewish victims. The trial hearings ended on September 1, 1946. On October 1, 1946, the judges delivered their verdict. They convicted 19 of the defendants and acquitted three. The judges of the IMT sentenced twelve defendants to death.

The IMT trial is the most famous of the war crimes trials held after World War II. During the five years that followed the end of the war, hundreds of thousands of Nazi perpetrators and their collaborators were tried by other courts in Germany and in the countries that were allied to or occupied by Nazi Germany.

The Allied military authorities, which now occupied the defeated Germany, began a process of denazification. “Denazification” included renaming streets, parks, and buildings that had Nazi or militaristic associations. It also removed monuments, statues, signs, and emblems linked with Nazism or militarism. Nazi Party property was confiscated. Nazi propaganda was eliminated from schools, the media, and churches. Nazi or military parades, anthems, and symbols like the swastika were prohibited. The distribution of Nazi propaganda continues to be illegal in Germany today.

- Learn: Read “Postwar Trials” in the Holocaust Encyclopedia.

What does the word Holocaust mean?

Holocaust is a word of Greek origin meaning “sacrifice by fire.” By the late 19th century, holocaust most commonly meant “a complete or wholesale destruction.” The word was used for a variety of disastrous events, including pogroms against Jews in Russia, the murder of Armenians by Ottomans during World War I, Japanese attacks on Chinese cities, and even fires.

As early as 1941, writers occasionally used the word “holocaust” when describing Nazi crimes against the Jews, but it was not the only term they used. After World War II, Holocaust (with either a lowercase or capital H) became a more specific term. By the late 1970s, it became the standard English word used to refer to the systematic annihilation of European Jews by Germany’s Nazi regime. In Israel, it is more common to use the word sho’ah, which is the Hebrew equivalent of “Holocaust.”

Why do we study the Holocaust?

The Holocaust was a watershed event, not only in the 20th century but also in the entire course of human history. Studying the Holocaust reminds us that democratic institutions and values are not automatically sustained. They need to be appreciated, nurtured, and protected. The Holocaust was not an accident in history. It occurred because individuals, organizations, and governments made choices that not only legalized discrimination but also allowed prejudice, hatred, and ultimately mass murder to occur. It also teaches us that silence and indifference to the suffering of others, or to the infringement of civil rights in any society, can—however unintentionally—perpetuate these problems.